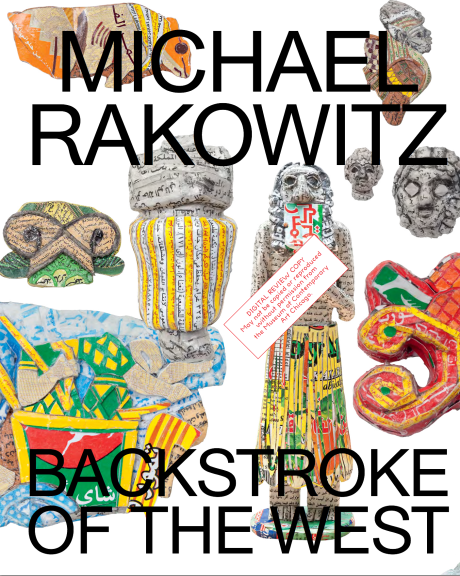

I was asked to write in Michael Rakowitz’s catalogue, for his show at the MCA Chicago (Sept 2017 – March 2018), entitled Backstroke of the West, curated by Omar Kholeif. Michael’s work encompasses errant history, near and far. He plays with time and matter. And so, here’s my short story inspired by his preoccupations*.

“I REMEMBER HISTORY,” she says.

“YOU REMEMBER NOTHING,” he replies.

A precious artifact separates them. It’s white, brittle looking, a real talking point. Dust falls onto the starring loan. Neither she nor he notices. It’s nearly midnight now. The museum is open late, for the public. We must educate the public. Guards are prone to daydream, but what do they dream of at night? Dust always falling, breeding, elsewhere in the building too. Tiny enemies. Dust falls between this woman and this man.

“I REMEMBER…,” she says.

“YOU REMEMBER…?” he shakes his head.

They have been visiting this popular museum since they first met, on the third floor, forty-five years ago. They sought shelter from the rain that day. From the fucking chaos of the world. Their eyes locked onto one another—through the missing gaps of a dinosaur skeleton. Love at first extinction, you might say. Small talk ensued. Were the dinosaur’s memories still trapped in the bones?

A tour guide passed by, arms flailing, and he shouted, “One day, humans will be artifacts in a museum like this.” It made our couple laugh, and, before long, they’d told each other their plain, familiar names.

“I REMEMBER AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIG IN…,” Riva says.

“YOU REMEMBER NOWHERE,” Okada side-eyes.

Time in a museum is unlike time on a watch, on a screen, between atoms. Museum time is a relatively affordable luxury, a holiday away from habit. Time, here, is not narrative. Neither is it nonlinear. It is formed of crystals, according to a Sudanese painter whose work they saw on the ground floor of the museum, in rooms one through four. Women trapped in crystalline cages.

“I REMEMBER MY MOTHER’S TIARA,” she says.

“YOU REMEMBER WRONG,” he brays.

Riva and Okada have lost track of their route through the popular museum, the rooms they’ve visited, in their long, winding life together. Numbers are related to counting, and, after some years, when their marriage slowly turned into a private museum, they chose not to count anymore.

“I REMEMBER OUR FIRST BED, IT WAS…,” she says.

“YOU REMEMBER NADA, SO WHY DON’T YOU…,” he coughs.

Earlier, in one of the museum’s other rooms, they read a caption that said, “Time, more than space, belongs to theologians, filmmakers, and shamans.” They made a note of this, in shorthand that the other would find impossible to ever read. Then they watched a film. Historical sites—thousands of years ancient, in a part of the world most associated with unending wars—were being blown up with old explosives. These statues, apparently, were sacrilegious. Shirk, the greatest sin of all. Shirk, attributing God’s greatness to something other than God. Destroying them was the duty of the devout?

But the videos played backward. Pulverized dust slowly congealed back into form and figure, poise and premonition. This is often how their marriage felt too.

“I REMEMBER THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC,” she says.

“THERE IS NOTHING TO REMEMBER,” he shushes.

Are we able to piece together their itinerary over the past three hours—or three decades, who’s to say—moving from curated room to didactic display? Is this an accurate checklist?

- MISSING ARTIFACTS STOLEN FROM

THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRAQ IN BAGHDAD. - LOST VOLUMES DESTROYED IN THE STATE LIBRARY

OF HESSE-KASSEL IN GERMANY - DISPLACED TRAY FROM THE GREAT SYNAGOGUE IN BAGHDAD

- SCALED-DOWN RECONSTRUCTION OF THE ISHTAR

GATE FROM ANCIENT BABYLON - DAMAGED BOOK OF PRAYERS

- IRAQI FEDAYEEN HELMET, CIRCA SADDAM HUSSEIN

- DARTH VADER’S HELMET DYING LANGUAGES

Doomed to repeat, cursed to repeat, shuffling the same playlist—this is what their grandchildren believe happens to civilization. Only technology changes. The nature of switches, dials, buttons. If humans are going to be artifacts in a museum like this, Riva wonders, could they pick me? She imagines a vitrine shaped like a crystal, like the one she saw Vladimir Lenin encased in, at his Red Square mausoleum. She envies the glory of his eternal rest. His pallor.

“I REMEMBER LENIN’S GUARDS. WERE THEY MADE OF WAX?” she asks.

“YOU REMEMBER EVERYTHING INSIDE OUT,” he says.

It is 11:59 pm, and the museum guards are rounding up people, politely asking them to make their way to the exit. The precious artifact separating Riva and Okada—white, brittle looking, a real talking point of today’s museum tweets—has puzzled them ever since they arrived.

The museum should provide theologians or shamans for moments like this, when the captions on the walls fall short. When you’re free-falling through meaning. When you look at the person you’ve spent almost your entire life with and— like that—you feel no love.

- TRAGEDY

- DISPERSAL

- DISPLACEMENT

- EXILE

- RECONSTRUCTION

- REMEMBERING

- FORGETTING

- FARCE

The chaos of the fucking world leads us here?

To a set of “keywords”?

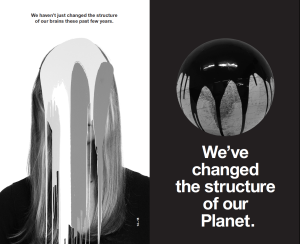

The precious artifact—says the exhibition handout—is a new, three-dimensional printed copy. Very twenty- first century, apparently. However. Let’s be honest. This re-creation is more of a lewd ghost, composed entirely of digital dust, the wet dream of millennials, who have become the stupidly successful museum’s priority audience.

Riva and Okada fail to lock eyes with one another, missing the dinosaur skeleton maybe, missing whatever it is that makes the past something other than a grotesque animal. Their memories are trapped inside their bones. And at this moment, sadness falls between Riva and Okada for the last time.

“I REMEMBER OUR HISTORY,” she says.

“MY LOVE,” he cries, “I KNOW YOU DO.”

*The characters’ names are borrowed from the actors’ names in Hiroshima Mon Amour, as is the contrapuntal affirmation and denial between the protagonists.

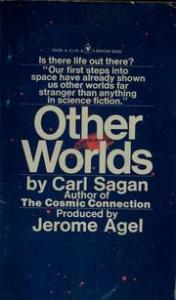

And here’s the cover of Michael’s catalogue: